I was finishing up a two week holiday in Bergen, Norway, when I decided to spend my last day checking out some of the historical sites in the city. The first on my list was Rosenkrantz tower, an imposing, largely Early Modern, but originally medieval, structure and one of a series of buildings on Bergenhus Fortress premises. The tours themselves were self-guided and this made me slightly nervous as I know that these older structures can be very confusing and its easy to get turned around. Especially with my exceedingly impressive penchant for getting lost in the simplest of locations. I had managed, just a week or so previous, to completely lose myself in the London Tube (Bank Station is now my sworn enemy).

After wandering the grounds and taking endless photos of the outside, my curiosity overruled my trepidation and I ventured inwards. Armed with my map, I made my way down the meandering stairs into the dank and creepy dungeon where I quickly snapped a few blurry photos and then sprinted for the next cramped, winding stairwell.

The tower was a maze with each level opening up to one room with multiple doorways spanning off into what seemed like an endless array of possibilities. The exhibition was excellent and I really enjoyed it while simultaneously panicking I was taking the wrong stairs, wrong door, or wrong room and would forever become lost. But it was on the way down, now ever-so-slightly more confident that I would not end up trapped within its ancient confines, that I stumbled upon a room I had missed.

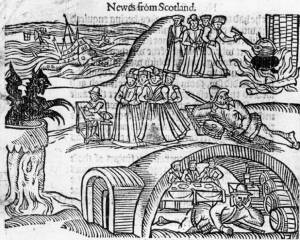

The room was dominated by large white posters of historical drawings, etchings and paintings. As I perused the room, I realized I was standing in an exhibition on Anne Pedersdotter, one of the most famous women executed for witchcraft in Norway. And it was this particular image that caught my eye.

Anne Pedersdotter was executed in 1590 in Bergen, a victim of the murderous witch-hunts that were burning through Early Modern Europe. She was the wife of Lutheran Minister Absalon Pedersen Beyer, one of the most famous humanist scholars in Norwegian history.[1] The charges against Anne represented a trend whereby reforming clerics were attacked through their wives because they themselves were too highly placed to be successfully targeted.[2] She was a rarity in that she stood trial not once, but twice; surviving her first court case largely due to her husband’s connections. But when he died in 1590 and could no longer protect her, the case was reopened, she was found guilty and tragically burnt alive.

One of the most interesting charges brought against Anne? That she cursed a man with illness because he refused to give her beer.[3]

The connection between witchcraft and brewing is one that a few scholars have recently explored. And while in Anne’s case, one of her supposed magical spells was angry backlash due to the refusal to provide her with beer, there may well be a link between the very women who brewed beer and these accusations themselves in England. As we saw in the post on Elynour Rummyng, in literature, alewives were depicted in association with witchcraft- making potions, being a sexual deviant, possibly being kin to the devil himself and even keeping the company of witches.

But what of the real-life women?

As both Bennett and Hester have argued, it is hard to know whether alewives were accused of being witches because they were alewives or due to their poor social position-little extant evidence remains to be able to discern this without a doubt. However, what is very clear, is that both the language used to describe alewives and accused witches, and the socio-economic position of the two groups, is remarkably similar, as we have seen.

Alan MacFarlane conducted a study of accused witches based on the Assize Records from Essex dating between 1560-1680 and found one woman had a husband who was listed as a beer brewer.[4] But, as we know, this might mean that they simply brewed together. This evidence is difficult to work with in terms of assessing relationship of witches and alewives because it lists only the husbands’ occupations, and with the exception of perhaps this woman, we do not know if the other accused women of Essex were also brewing in some capacity. Or even if they were, whether the accusations stemmed from this trade.

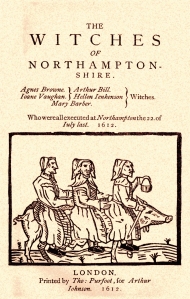

However, MacFarlane contended that witches tended to be poorer than their alleged victims, with yeoman making up the majority of the occupations of the husbands listed.[5] This reflects the arguments by Hester, Bennett, and others, that the women who were accused of witchcraft tended to be the most vulnerable in the economy- laboring women, widowed, possibly older, and poor; or those in competition with men for trade and money.[6]

And it was overwhelmingly women who were accused and murdered for witchcraft. According to Christina Larner, the reliable figures put the percentage in Germany, France, Switzerland and Scotland at 80% female and in England and Russia somewhere around 95-100%.[7]

Early Modern England saw a rapid population increase. This was coupled with both a female majority and decreasing means of livelihood for women, resulting in an increased impoverishment and dependence by lower class women, also known as the feminization of poverty.[8]

And this decreasing economic position is reflected in the status of female brewers. Bennett believed that the increasing masculinization of the brewing trade led to a new financial balance between spouses, and unmarried women were particularly negatively affected when they became less able to compete with couples.[9] In turn, those women who were still able to compete on some economic level, largely widows, were a threat to this new balance and male dominance in the trade, and thus became targets for witchcraft accusations.

And we do know that men were deliberately spreading rumors to force women out of the brewing business. For example, In 1413 Christine Colmere’s business was totally destroyed when Simon Daniel told all her neighbors that she had leprosy.[10] A further example dates to 1641, this time of an unnamed widow, brewing at the Ludlow castle garrison, who found her entire trade to be lost when a male competitor spread false rumors about herself and her business.[11]

How common or how widespread this phenomenon was is something for further research. However, as was seen with these cases, it is clear that accusations were deployed as a means of social control, which is mirrored in the way witchcraft charges in the case Anne Pedersen and others. So it is not too much of a stretch to speculate that accusations of witchcraft might also have been deployed as this means of controlling poor alewives in England.

Except of instead of a business going under, they could lose their lives.

While we may never truly know if alewives were accused of witchcraft simply because they were alewives, it is clear that women who brewed were perhaps particularly vulnerable to the witch-hunts. This could be because they were competing with men in a trade that was increasingly being masculinized which led to accusations to force them out. It could also be because these brewsters were largely poor, single, and/or widowed, much like the larger population of people condemned for witchcraft, and this left them without the valuable social and economic resources needed to combat such accusations.

In any event, there is a clear and large overlap between the women who were alewives and those accused of witchcraft. One that could very well have led to their demise by the ever-virulent witch hunting spree that gripped late medieval and Early Modern England.

Sources:

[1] Brian P. Levack, ‘The Chronology and Geography of Witch-hunting’ in Witchcraft and the Supernatural (Routledge Freebook), p.71.

[2]Levack, ‘Chronology’, p.72

[3] Ibid.

[4] Hester, Lewd Women and Wicked Witches: A Study of the Dynamics of Male Domination (Routledge, 1992), p. 162; Alan MacFarlane, Witchcraft in Tudor and Stuart England: A Regional and Comparative Study (Routledge, 1999) p. 150.

[5] MacFarlane, Witchcraft, p. 150.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Christina Larner, ‘Was Witch-Hunting Woman-Hunting?’ in Darren Oldbridge (ed.) The Witchcraft Reader (Routledge, 2008), p. 274.

[8]Marianne Hester, ‘Patriarchal Reconstruction and Witch-hunting,’ in Darren Oldbridge (ed.) The Witchcraft Reader (Routledge, 2008), p. 283.

[9] Judith Bennett, Misogyny, Popular Culture and Women’s Work,’ in History Workshop Vol. 31 (1991), p. 182.

[10] Judith Bennett, Ale, Beer and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World. 1300-1600, (Oxford University Press, 1996), p. 135.

[11] Bennett, Ale, pp. 135-136.